Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) and Upfront Embodied Carbon

By Gavin White & James Morton

In response to growing environmental concerns, the construction industry is increasingly recognising the need for sustainable practices. Modern Methods of Construction (MMC), has emerged as a promising approach to achieve sustainability in this field, so much so that it has been heavily involved in the UK Government ‘Construction Playbook’, where MMC has taken precedence over embodied carbon calculation, with ‘MMC’ mentioned twenty-seven times more than ‘embodied carbon’.

MMC encompasses a range of innovative construction techniques and materials that provide alternate approaches when compared to traditional building methods. However, the effectiveness of MMC in reducing upfront embodied carbon when compared to conventional practices is not fully understood, as per the survey conducted as a part of this study, despite being widely reported, and case studies are sparse.

This article aims to bridge this knowledge gap by conducting a comparative analysis of MMC and 'typical' construction practices, specifically focusing on their impact on the upfront embodied carbon for the structural systems of MMC. Real-life projects utilising MMC have been studied, and a counterpart to these projects using conventional RC in-situ flat slab construction has been developed as a baseline for comparison. The study looked at the effectiveness of steel modular, precast concrete, and engineered timber, in comparison to the Reinforced Concrete (RC) in-situ counterpart. Additionally, a survey involving 40 construction industry participants, ranging from designers, contractors, MMC advisors, and sustainability consultants, was conducted to gauge their perceptions of MMC and its sustainability impact. The survey findings will be presented and discussed in the article.

MMC Techniques explored in this study.

By contributing to the ongoing discussion on MMC and sustainable construction practices, this study seeks to raise awareness and understanding of these methods. The study's results will hold significant value for policymakers, architects, engineers, and construction professionals involved in designing and implementing sustainable construction practices. Ultimately, the goal is to foster the adoption of MMC only where appropriate and promote more environmentally friendly practices within the construction industry. However, it is important to note that this report will solely focus on the upfront embodied carbon aspect, excluding other potential impacts such as resource consumption, operational energy, and biodiversity net gain/loss, which are nonetheless very important to consider.

MMC and Sustainability

MMC encompasses diverse construction techniques, currently emphasising offsite construction and innovative technologies. MMC aims to enhance efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability when compared to traditional methods. It's noteworthy that offsite construction, a key component of MMC, has been in use in the UK since 1945, particularly in addressing post-World War II housing shortages.

MMC includes various methods such as modular/volumetric, prefabrication, panelised, and pre-assembled construction. By relocating a significant portion of construction work to a controlled factory environment, MMC offers advantages such as reduced waste generation, improved output quality, heightened construction efficiency, reduction of the on-site program, and overall cost reduction. Waste reduction plays a significant role in MMC's sustainability, particularly in reducing structural material wastage on-site (module A5.3, previously referred to as A5w in How to calculate embodied carbon) and emissions due to general construction activities (module A5.2, previously referred to as A5a).

Prefabrication, a core element of MMC, has demonstrated impressive waste reduction, with one paper reporting a reduction of 90% of waste when compared to traditional on-site construction [1]. Also, there is an expected 50% reduction in construction time [2], although lead-in times may be larger to account for off-site manufacture, offered by MMC, and when combined with the waste reduction there is a perceived large reduction in A5.3 and A5.2.

Percentage of total embodied carbon for concrete and steel. (Values taken from IStructE 'How to calculate embodied carbon')

However, it's essential to contextualise waste reduction benefits. The total emissions attributed to waste during construction are relatively small for concrete (in-situ) and steel sections, at 5% and 1%, respectively, highlighting that the significance of waste reduction provides little impact to the overall embodied carbon of these materials.

Regarding site activities, the current RICS ‘Whole life carbon assessment’ [3] guide states that a baseline figure of 40kgCO2e/m2 should be used for construction activities on a project, with any offsite construction being considered in the A1-A3 modules. Although this figure would typically be time, activity and project dependent, with this current method of calculation no carbon benefit would be noted by using MMC. However, it is clear to see that a reduction in construction time and activity would be beneficial in terms of carbon.

Survey Results

A poll of 218 construction industry professionals aimed to assess perceptions of MMC's impact on embodied carbon reduction. Results showed that 59% believed MMC reduces embodied carbon, 15% were unsure, and 26% disagreed, revealing uncertainty and scepticism. A focused analysis of 40 responses echoed these findings.

In the focused analysis, MMC was found to be primarily used in fewer than 20% of design briefs (73% of respondents), but 65% reported using MMC in over 20% of ongoing projects, suggesting design team influence over client preference. Opinions on the most sustainable MMC method varied: modular/volumetric construction (38%), engineered timber (25%), and precast concrete (5%) were top choices.

Most notably, 88% agreed MMC will see increased adoption, but 100% expressed a need for more research to inform decisions, meaning we could be in a situation in the future where we are heavily implementing a process that has relatively unknown nuances.

Case Studies & Upfront Embodied Carbon

Three authentic case studies were examined to evaluate the application of MMC, contrasting them with an in-situ RC counterpart. These case studies represent real-world projects where MMC was predominantly used as the primary structural element. At Ramboll, we conducted assessments and devised an RC frame with matching floor plans and a similar grid pattern to closely replicate the MMC structures. This approach allows for a direct side-by-side comparison, avoiding the need for comparisons to industry standards or other benchmarks.

Importantly, the comparison endeavours to exclude elements that are interchangeable between both materials; for instance, the same concrete cores have been utilised in both the modular and precast case studies, with the engineered timber comparison replacing the timber core walls with concrete. Furthermore, the analysis exclusively concentrates on the superstructure of the projects, without considering how alterations in structural mass impact the substructure design. The RC in-situ carbon value are not comparable due each project having different GIA, spans, depths etc.

All data regarding embodied carbon has been sourced from the IStructE ‘How to calculate embodied carbon’ [4](HTCEC) guide or the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) ‘inventory of carbon and energy’ [5] database while calculations were compete using the IStructE ‘Structural carbon tool’ [6]. Notably, all in-situ concrete used in the comparative analysis contains 25% cement replacements. Waste factors from the HTCEC have been used, which already contains values for engineered timber and pre-cast concrete. Although off-site construction for steel would in theory reduce less waste, a large proportion of our steel structures are already fabricated off site and arrange on-site, meaning there would be little difference in the waste accumulated between the steel section values in the HTCEC guide and for steel modular.

Modular Construction

The examined residential development employs standardised modules for its superstructure, comprising closed-section steel columns, open-section steel beams, steel bracing systems, and composite decking for floors and ceilings. Notably, these modules are intended for installation through lifting, necessitating the incorporation of supplementary steel elements to meet the associated loading requirements.

The RC alternative employed a comparable grid spacing to maintain consistency in room layouts within the development. This resulted in an approximate 5m x 7.5m grid utilising a 275mm in-situ slab and 500x500mm square columns. The presence of an RC podium beneath the modules in the original design has potential relevance to both structural systems, but for the purposes of this comparison, its impact has been omitted. Additionally, the development features two substantial concrete cores and it is assumed that the concrete slab can convey lateral loads to the cores via a diaphragm mechanism.

Modular Construction

The primary difference in carbon values lies in the A1-A3 range, indicating potential reductions in structural efficiency within the modular scheme.

Modular construction derives cost and time efficiencies from the rapid manufacture of uniform products, akin to the automotive industry's product lines. Consequently, buildings ideally comprise a limited variety of module types distributed across the floor plan. This can lead to a suboptimal design for certain elements, as not every component is tailored for maximum efficiency (more so than RC design) or modules are designed for multiple design cases i.e. transportation and lifting. In contrast, in-situ RC frames offer more flexibility in element design based on utilisation, allowing for a leaner design approach.

Minor variations between the two schemes are evident in transport and waste emissions. The transport efficiency of materials to the site is notably higher for fully assembled modules compared to concrete and single steel sections. While these factors represent a small proportion of total embodied carbon, they could assume greater significance as we aim to decarbonise construction material production. Waste reduction is also substantial for modular construction, presenting a critical aspect in our quest to minimise material consumption and production.

A4 emissions calculation was conducted manually for the modular scheme, due to the carbon factors in the IStructE tool and guide based on transporting individual elements. However, it's essential to recognise that transporting modules to the site may be less efficient than delivering single steel sections. An internal analysis by Ramboll, surveying major steel fabricators in the UK, revealed that steel transportation is typically around 80% laden during outbound journeys. Fabricators commonly use articulated lorries with a capacity not exceeding 33 tonnes, resulting in an average delivery load of 28 tonnes. In contrast, the average module weight, comprising steel beams, columns, and profiled decking, is approximately 6.8 tonnes. Consequently, delivery efficiency in this scenario is around 21%, signifying a notable 59% efficiency disparity. It has also been assumed that the return journey of the lorry for the modular case is 0% laden. Although, many modules may come already fitted with internal partitions and services, meaning there may be a reduction in deliveries, and hence carbon emissions associated with deliveries, for other elements that make up the final building.

This study focused exclusively on modules A1-A5 concerning carbon associated with these schemes. It's worth noting that modular construction offers substantial potential for complete reuse at the end of its life cycle, achieved by disconnecting and repurposing the modules.

Precast Construction

The presented case study employs a combination of in-situ concrete and precast elements, incorporating two-storey precast columns and precast slabs. The slabs feature a protruding triangular lattice design from a thin concrete slab, enabling a self-supporting system with significant reinforcement integrated into the slab itself. Only a top layer of in-situ concrete is poured over the slab with mesh reinforcement, facilitating rapid erection and eliminating the requirement for formwork—typically needed for conventional in-situ frames.

The counterpart RC scenario maintains a similar grid spacing to enable a direct floor plan comparison. In this context, it is assumed that the stability system of the original structure—comprising RC stair cores and RC shear walls—remains appropriate for the in-situ design being considered.

The IStructE Carbon Tool does alter both the waste factors and transport emissions when comparing in-situ and precast concrete. Both of these values have been used in this calculation to note the difference in emissions for both construction techniques.

Precast Construction

Our study revealed similar figures for precast and in-situ approaches, yet some distinctions warrant consideration. Modules A1-A3 exhibited a slight reduction in embodied carbon for in-situ, attributed to the use of 25% GGBS, while precast commonly uses minimal or no cement replacement.

Transportation increased for precast due to element size constraints, unlike in-situ where overall mass governs transportation needs. Analysing waste, on-site concrete over-ordering is prevalent, resulting in doubled embodied carbon compared to precast. This underscores the significance of precision in concrete volume management to minimise waste. Our findings emphasise the need for a comprehensive assessment that considers diverse factors, offering a nuanced perspective on the environmental implications of construction methods.

While this study suggests a small difference between the precast and full in-situ options, other influencing factors may drive the choice between the two. The selected case study is located in a space-constrained environment, where rapid construction holds significant importance. The integration of the lattice structure along with precast columns helps mitigate delays associated with concrete curing during vertical progression, thus hypothetically streamlining the construction timeline.

Engineered Timber

The focus of our analysis is a residential structure designed primarily with a CLT system, prominently employing CLT slabs and cross-wall construction. The stability strategy for the CLT structure involves the strategic placement of CLT cores of varying heights, positioned throughout the floor plan to correspond with different levels. In our in-situ design approach, we emulated the core placements, replacing the CLT walls with RC walls. The engineered timber required some additional features to the structure to be compliant from a fire, acoustic, and vibration aspect, the use of plasterboard and screed flooring has been included in the calculation.

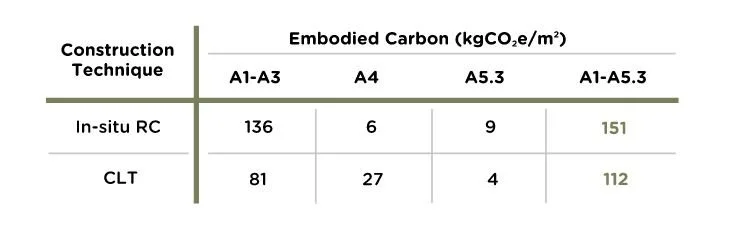

Engineered Timber

Here, a notable reduction in carbon emissions is evident with the adoption of engineered timber, attributed to timber's lower carbon intensity compared to concrete.

The figure for A1-A3 emissions does include an estimate for steel connectors across the structure, producing a 2 kgCO2e/m2 emission value. This calculation considers screws, nails, and brackets used for connectors. While the exact embodied carbon for these members is unknown, these estimates, using the emission factor for mild steel and the volume of steel used, represent a small proportion of the overall emission value. Similarly, to meet fire standards, plasterboard and screed were used throughout. The extent of the use was to have 2x12.5mm plasterboard on each side of a wall that was internally facing (i.e. 4x12.5mm for internal walls and 2x12.5mm for external walls) while 2x12.5mm plasterboard was used on the soffit of the slabs, with a 65mm screed and resilient floor finish on top. This led to 22% of the A1-A3 emissions being associated with finishes that were required to meet standards at this time.

Transportation has an increased embodied carbon mainly due to the large panels that make up the structure, leading to the transportation of materials being determined by the size of the materials rather than the mass, usually reducing the efficiency of the transportation process.

In terms of construction timeline, timber often offers a swifter process compared to concrete due to the latter's lengthier setting and hardening period. Despite this advantage, reservations linger regarding timber usage in construction. Concerns related to fire safety, insurance coverage, and overall expenses come into play, especially considering concrete's established reputation as a dependable, economical construction material.

Discussion

In conclusion, our study has illuminated the positive aspects of MMC when compared with conventional construction processes. However, it is essential to note that the carbon comparison does not consistently favour MMC in all cases. Construction projects operate within intricate ecosystems laden with multiple constraints, and it is within these complexities that the preference for MMC may emerge more prominently.

While there is a compelling case for embracing MMC in our journey toward a sustainable, and optimistically, a regenerative industry, this research underscores the critical caveat that MMC may not be universally applicable as the most sustainable solution for every project. As structural engineers, our responsibility lies in conducting thorough due diligence, consistently engaging in comprehensive optioneering studies to discern the most sustainable structural system tailored to the unique requirements of each project.

The study has clearly showed there are positives to the use of MMC when compared to typical construction processes, although in these cases the carbon comparison has not shown to always be favourable to MMC. Although, construction projects are complex ecosystems with multiple constraints which may lead to the use of MMC being more favourable. There is a clear case for the use of MMC as we progress towards a sustainable (and more hopefully a regenerative) industry, but this study has highlighted that the application of MMC may not be the most sustainable for every project. As structural engineers, we should always complete our due diligence to conduct comprehensive optioneering studies to find the more sustainable structural system for each project.

In the context of modular construction, our observation is that the efficacy of the structural system is sometimes underutilised. The time and cost economies of modular construction stem from its systematic and automated processes. Hence, employing modular construction for unique, customised projects might not be the most suitable approach. Structures that can be replicated and adapted to different applications, like schools and social housing, are poised to capitalise on the strengths of modular construction. On the contrary, our case study underscores that the capacity to repurpose modular structures presents a particularly promising aspect compared to other building materials. Designing modular structures for transient use and subsequent reutilisation could open up a sustainable trajectory for the industry, encompassing structures like temporary housing, event-based sports facilities, and hospitals.

While our comparison between RC in-situ and pre-cast cases revealed minimal differences, it underscores the importance of a nuanced evaluation for each construction method on a project-specific basis. Although the pre-cast option exhibited a higher embodied carbon, it is crucial to acknowledge potential localised advantages that may not be immediately evident. Factors such as enhanced on-site safety, reduced construction time translating to a more streamlined schedule, and a decrease in toxic fumes released into the local environment deserve consideration. Moreover, as we navigate the path toward sustainability, a pivotal aspect lies in the exploration of increased cement replacements, a measure that holds the promise of substantially reducing the embodied carbon associated with these construction processes. The quest for more environmentally friendly practices calls for ongoing scrutiny, adaptability, and an unwavering commitment to refining our construction methodologies.

Utilising timber is undoubtedly advantageous in curtailing embodied carbon, as widely acknowledged by multiple sources. Nevertheless, engineered timber's efficacy hinges on its appropriate usage. Our internal studies at Ramboll have indicated challenges in implementing timber within laboratory spaces due to stringent vibration requirements. The industry discourse has also highlighted concerns about structural efficiency for tall timber buildings, fire safety, and insurance implications. This underscores the importance of selecting the most fitting method for each specific project.

Through this article, our aim is to kindle discussions and promote action within the industry. We advocate for heightened research and collaboration to enhance our comprehension of existing construction systems and determine the apt application of each method. If anything, this study has helped highlight the nuances of the construction processes and the lengths that are still required to truly understand our impact on the environment. At Ramboll, we're committed to being at the forefront of MMC, using it where appropriate and carefully considering options through thorough analysis when MMC is being considered.

[1] RICS. (2023). Whole Life Carbon Assessment. p.g. 82

[1] WRAP. (2018). Waste Reduction Potential of Offsite Volumetric Construction. Oxon: Waste & Resources Action Programme.

[2] Bertram, N., Fuchs, S., Mischke, J., Palter, R., Strube, G., & Woetzel, J. (2019). Modular construction: From projects to products. McKinsey & Company: Capital Projects & Infrastructure, 1-34.

[3] RICS. (2023). Whole Life Carbon Assessment. p.g. 82

[4] O P Gibbons, J J Orr. (2022). How to calculate embodied carbon. Institution of Structural Engineers.

[5] Institution of Civil Engineers. (2019). Embodied Carbon – The ICE Database.

[6] Elliot Wood. (2022). The Structural carbon tool. Institution of Structural Engineers.